Heroes may have great victories and great defeats; their very lives and activities may ring with significance, but for most of us, life is much closer to the edges of meaninglessness. Except for our dreams and fantasies, our lives usually consist of small victories and small defeats. We are much more likely to see our lives as a series of cunning blunders, self-imposed traps or fortuitous ventures than as cosmically significant morality plays. So, Trickster is also a constant reminder of the marginality and liminality of our personal experience…

C. W. Spinks Jr.

Contents

He Is a Legend in His Own Mind………1 – 16

Commentary……………………………………17 – 25

References………………………………………26

Photographs……………………………………1 –

He was born in 1969 at a time when nothin’ was easy and everything was really tricky. Now, let me start out by tellin’ you, he wasn’t a bad boy, I’m tellin’ you, he just had to get along like everyone else. The problem was, he knew just about better than anybody else how to do it. His little brain worked over time, woke him early, kicked him out the door and got him busy on just about anything that he happened to run into.

Why, by the time he was just a little guy, he was hustlin’ and bringin’ his abuelita five pesos a day just pickin’ up cans; even then no one believed anythin’ he said. You see, he was not his mami’s favorite son. He carried papi’s blood inside a’ him and that man, he never stayed around long enough to give any love at all. But if you were to look at him, you’d wonder why nobody wanted him; long legged and skinny, a bright-toothed smile and soft black curls, but those eyes all by themselves sometimes kept him out a’ people’s good graces. “Cat eyes” they called him, cluckin’ their tongues and they’d kick him right out a’ the house when they’d turn that yellow green color. “Evil eye”, they said.

No, that’s right, he wasn’t to blame, and he didn’t mean to harm nobody, he just did, not meanin’ to, but never ever in a bad way. But because a’ all this, bein’ alone and all, he called himself el hijo preferido de Shango. But it was his bad luck, people around him didn’t yet know that. It’s often and plain as day that people afflicted come to have a special gift, a way a’ turnin’ your life upside down for no better reason but to teach you some a’ life’s lessons. But who knew? He was just kicked around ‘til he got kicked out, but that didn’t bother him; well, not that anyone could tell, or not that anyone cared. He had a mission to do, he said, and, by god, if you get in his way you’re about to have a little a’ his medicine and it just might hurt a little goin’ in and comin’ out, but that wasn’t his intention, you know. He was just tryin’ to live, doin’ the best he could with what he had in his hand, plantin’ seed right where he stood, like his abuelito used to tell him to do, lookin’ for opportunity and then grabbin’ the fruit when it is full and ripe and juicy sweet. Well, he had to, or he just never would a’ got nothin’ at all.

Now, I can just see him, you know why? Because he was a good storyteller, a real good storyteller. He is so good that most a’ his friends call him a liar. They just plain don’t believe that what went on, goes on anywhere to anybody. But me, I’d lay perfectly still when he’d start up with one a’ his crazy, tilted, funny stories a’ his boyhood all mixed up and full a’ sadness. Sometimes I’d be wipin’ my eyes from laughin’ so hard and from time to time I’d be cryin’ and tryin’ to hide my sobs. Well, if I were to tell the truth, in that dark room I could see his eyes all shiny with a tear or two, too. Well, like the time he told me: his mami sent him to the store to get milk. Now, milk was hard to get and precious. He left with a few pesos held tight in his young brown hands. He was just startin’ to grow and was feelin’ all like a man, at least inside a’ his pants he was. The girl, whose dad ran the store, fit his fantasies just right; his favorite, a mulatta, skin like dark honey, black hair all glisteny, a big round ass and tits that hardly stayed inside a’ her clothes. She was full grown, all a’ seventeen years old and a good head and shoulders taller’n him. Well, while he waited in line with the other kids and abuelos and mamis with bebes, he couldn’t take his eyes off’n her. Everything she did made him tingle all over. Well, at his turn he grabbed the bottles from her and turned so fast he dropped both bottles right there in front a’ her and all a’ them, milk and glass all over the floor. He dropped to his knees knowin’ what was goin’ to happen when he got home. Wobbly and shakin’, he started to pick the glass up. “Stupid”, he thought, “stupid, stupid, stupid”. Her thighs and arms and breasts were so close he could smell them before he saw her squattin’ to help him in that too short, too low, too tight, barely-there dress, knees open, givin’ him just a peek at what he had only guessed was there. Well now, you can imagine, he couldn’t say not one thing. He was a pitiful mess and in a heap a’ trouble. Even if he had the want to right now, he, no way, could say anything that would a’ made any sense; and he knew he looked pitiful too. His heart fairly beat the drum right out a’ his chest, blood rushin’ ‘round god knows where and all up in his face makin’ him look like a cherry sucker on a neck. What’s worse is how the people stared. But right there they took up a collection and bought that poor kid two more bottles a’ fresh milk that they could barely afford themselves. What he didn’t know was that his mami had been standin’ right outside that store watchin’ the whole thing through the window, because, you know, she never did trust that boy. Well, he high tailed it home and it didn’t matter that he came with the milk in his hands; the blows that he got that day didn’t hurt so bad rememberin’ how she smelt and how beautiful she looked. Three days in bed weren’t so bad with that on your mind.

And then what about that time he was invited to a party by his friends at school? Now, as he tells it, they were neither poor nor rich. But he didn’t have any clothes. All he owned was his school uniform, and abuelita had bought that, a few pairs a’ scruffy shorts and a pair a’ sandals. Why he never had a birthday party and never owned a bicycle. As a matter a’ fact, he didn’t even have one picture a’ him as a baby or a kid. But Robertico did, and Maricela did, and the baby did too. They had papis who kept them in clothes and love, even if they didn’t live there anymore. But for what he did every day, he figured he had plenty to wear on that hot island. But the blood was risin’… he’d now reached fifteen… and girls… and the music… enough said. He knew in a drawer in his mami’s bedroom was a pair a’ brand new pants that she was keepin’ ‘til Robertico grew big enough to fit in. So, while everyone was gone that afternoon, he snuck right on in that room and stole them. Them and a shirt and pair a’ shoes from the babies’ daddy. He hid them under his bed and when the sun was just startin’ to drop out a’ sight behind the palms, he pulled them out from under the bed and put them in a bag and slyly made it out a’ the house. He put them on and no importa that they were a little big; he felt fiiiine. Well, the night got a little wild, like they oft’n get when you got boys with the blood risin’, stars shinin’ in the sky, night birds singin’ and air that you can’t even feel it’s so close and full a’ smells a’ dirt and swamp and sweet, sticky flowers. As you might a’ already guessed, he tore those pants. Oh yeah, he got them back in the drawer alright, but he spent his days and nights prayin’ to the gods and all the spirits that his mami would forget all about those pants. But his luck hadn’t come yet and one day when she had time on her hands, she decided to sew those pants to fit Robertico. Well, he got bounced off’n the wall a couple a’ times, but while he laid there in bed he didn’t have mami on his mind. But he never either forgot how to cry or to hope for better times comin’. And anyway, some things don’t hurt so bad when you got things to do. I mean he’d become accustomed to punishment. He had to hide in the back a’ the truck to get to go to the beach with the rest a’ his cousins or they’d kick him out, right out on the side a’ the road to find his own way back. He got set in the ant tree one time, three hours he sat ‘til the neighbor lady came and got him out. He was covered from head to toe in bites that burned like live fire, poor child. He got beat up at school, and kicked out too. And even his own mami told him to go away. Some things hurt less than they teach you. But those are hard lessons, hard, hard, hard lessons but you learn them real good. That’s why he was on his own at fourteen, don’t you just figure. That’s why he learned real fast to hustle. A cracker-jack mechanic he is, a bricklayer, truck driver, carpenter and a beer seller, hotel-worker, painter, plumber, a jack-of-all-trades he is. And more than that, the boy can dance. He is like the finest piece a’ work that Olodumare ever has made. He grew up so pretty; so fine, I say, that all his parts worked so smooth that you’d swear he was dropped on this earth by accident. When he danced you never knew what to look at; it all waggled, it rocked and swayed, it twisted in and out and you could feel his rhythm inside a’ you even if you was just watchin’, and he won you over even when you were resistin’ with all your might. Everything, all he knows how to do didn’t take effort to learn, it just came natural to him.

I guess it was all this that made him what he is. Instead a’ turnin’ him mean… well, no one could ever really say he was mean, it turned him nice. Well, nice just isn’t right either, well, just maybe not in the way some folks might understand it. Sometimes I think he’s so nice that he didn’t know when someone didn’t like him, because it seems like to me, if someone don’t like you, you just stay away. But not him, why, he always just did the damned opposite a’ what you thought he ought’a do. If you didn’t want him around he’d even be more nice, smilin’ and lovin’ you so you just had to let him in like a little puppy snappin’ at your heels.

Now, that’s just what he did to me and I’ve seen him do it to enough folk that I know he ain’t stupid. I think he just sees the opportunity in everything and in everyone. Not in a mean or evil way, but just like I said before, his abuelo taught him a fine lesson: plant where you are and don’t leave one hole empty and then in time, reap the harvest. If you cross his path, he takes you in and he just never lets you get away. He stays with you through the endurance. Yeah, it could get a tad annoyin’ but he seems so innocent you can just fall right under his spell, like he’s got some special kinda’ charm or somethin’ and the next thing you know, he’s there changin’ the furniture around, takin’ charge a’ the stereo, whippin’ up something to eat and washin’ your car and drivin’ it too. But there I go, gettin’ ahead a’ myself.

It took him a while, sleepin’ in parks, and sometimes even sneakin’ in to sleep like a little puppy, all cuddled up in a heap with his cousins, to get his bearings about him and make some money. It was then that he learned to fly by the seat a’ his pants. Well, to hear him tell it, he always had money a jinglin’ in his pockets and plenty a’ friends to boot. He wasn’t a wise guy, but he wasn’t stupid either. He just never let nothin’ get by him. Every time he got beat down was a chance to get somethin’ out a’ it. He studied people and took a lesson. Well, now it’s common enough to learn from them that are older than you and that’s just what he did.

He was sellin’ garlic on the street and coffee beans too, dodgin’ the police and outta the blue comes an old woman who grabbed him right out a’ his business and said, “Mi vida, you can either live like you’re doin’ or you can learn another way”; and she took him right off’n the street tellin’ him, “Mi rey, you’re too good to be livin’ like this”. Now, she didn’t know him. But she saw him. And it was here he learned her magic. Here he gathered up all the wisdom he carried around in his head. Stuff he’s not ever gonna forget; like she told him, there’s spirits that are walkin’ all around us, old, ancient folk that if you keep eyes and ears open they might, if they have a mind to do so, and they got a reason to, they’ll tell you everything you need to know because that’s where they talk to you, right there in your own ears. Why, he knows about graveyard dust and dead people’s bones. He can tell you what you can do with salt and roots and feathers, string, chains and mud too, if you really want to know, and other worlds under this earth and all around even in the sky overhead. But most a’ all he learned patience and resistance and that nothin’ is written and that death can’t scare nobody if you know these things. Well, anyhow, that’s what he told me.

When he told me this, I thought he was talkin’ about the army or something. This was his time, he said, to study with madrina. “But what kind a woman is this?” I asked myself. He got buried in the earth one time with just his nose out and a jar a’ water buried beside him with a tiny little hose to drink out a’ and he couldn’t move a muscle. He got burned and learned not to scream bloody murder too. Resistance, he called it. Why, I even saw him one time hold a cigar on the soft skin, you know, between his thumb and the pointin’ finger and he never even flinched or made a peep. Everyone standin’ around yelled and hollered though, while he threw his head back laughin’ almost evil like so that it scared us. It didn’t hurt though. At least he said it didn’t.

Well, that was way before he ever walked through my door. But by that time, by my notion, he’d about lost all a’ his common sense, but gained some sort a’ extra sense. I never could figure it out what it was, but he seemed to see straight through situations and people and could slip right through cracks that you couldn’t see yourself and got himself out a’ all kinds a’ trouble that other folks would have to pay for. He seemed extra smart and powerful too in some sort a’ way, or maybe he was just lucky or goddamned blessed. Before he got here he knew how to get along all right. When he wanted somethin’, he got it. He may a’ had to steal it or finagle some way, but he got it when no one else could, even if he had to tell a little white lie or go against the law. Well now, I don’t believe he ever killed one a’ Fidel’s cows but if he did he would a’ been one among the multitudes.

There was the time that tio Gil sat in his rockin’ chair stewin’ about that he didn’t have a pig to roast Año Nuevo; because that’s the biggest day a’ the year you know, and this was the first and the only time he ever passed a New Year without stickin’ a pig, feedin’ all the family, neighbors and friends. Well, he was mighty depressed, and no one was gonna pull him out a’ that deep hole he was in. He started swallowin’ rum and pullin’ on that cigar at daybreak and it seemed like nothin’ was gonna stop him, because as custom would have it, early in the mornin’ all the men a’ the family would gather in the patio in back a’ the house and dig a big hole big enough to throw the big old pig in that you’d been keepin’ back there for just such an occasion. Well, they’d fill the roastin’ hole with round smooth river rock and lots a’ wood and set it all a blaze. When it got down to red-hot burnin’ coals they’d lay banana leaves on top. Then someone would take a sharp knife and stick that pig right in the neck. It’d be so swift, that pig dropped to his knees like he didn’t see it comin’. They bled it, gutted it, then threw it on the fire and covered it with more leaves and dirt and they’d just leave it there almost ‘til midnight. By that time the pig was so sweet and juicy and crisp on the outside that the kids’d be fairly jumpin’ out a’ their skins wantin’ to grab some a’ that. Then they’d grab it out a’ the fire and carry it into the house and drop it onto the table. Then the women would bring out the congri, yucca, tostones and lots of other good stuff. This they planned all year long. So now you can see what I’m talkin’ about, times were hard all around if you couldn’t get a pig in the backyard.

Well, so that young man, just barely a man, by man world standards, talked a friend of his into takin’ him out to the mountains. It was there he found a woman smokin’ a tobacco with three pigs just sittin’ up on her porch like they were sharin’ a right nice mornin’. Well, like I said before, he was a real good talker and he began to relate the terrible state tio Gil was in. And right there that crony said, “Take the one you want son and don’t give me nothin’ in return and god bless us both.” Well, they loaded that big pig into the backseat a’ the car and he sat up so pretty that you’d think he was gettin’ a ride in a taxi cab for sure, just lookin’ out a’ the windows takin’ in the sights ‘til they pulled up in front a’ the house and tio Gil shot out a’ that chair like somethin’ bit his ass. Can’t you just imagine the shoutin’ that went on?

Well, times were tough and that’s for sure and he figured to slip off’n that island just as pretty as you please just to see what lay on the other side a’ the sea. He laid a sure-fire plan. But like most sure fired plans there’s a hitch somewhere along the way and that young man sure enough found it easy. Runnin’ out a gas, he nearly died when the little boat he was in was swept under the bow of a great big coast guard boat hidin’ right where you’d least expect to find it. At that divine moment, a big white boat came up beside a’ him and threw a chain and hooked him, sure as you please, and pulled him out a’ death’s grip and threw him right into prison. Well, it was like prison: barbed wires, officers in uniform and nothing to do but stay; and imagine it, right there on his own beloved island.

Well, wouldn’t you think, anyway I thought, that this would be the final blow, but not for him. He started to figure out a way to make it all work for him right then and there. In fact, he worked so hard and smiled so hard that they put him in charge a’ the dispensary, writin’ him letters of commendation and all, signed captain this and captain that and sergeant so and so, and he ended up the best-dressed goddamned refugee there. Why, he had his own room, a radio and T.V. and free range of the whole damn camp. Why, he fairly had everyone eatin’ out a’ his hands. Well, he was a good gambler too. He played tripar like he was raised in a casino and nobody back home was ever able beat him. They never had any money while they waited in that holdin’ camp but he held all the cigarettes, you can bet your bottom dollar on that one you can. And you can say that gave him some power that you just can’t find any other way.

Well, I’d like to start out by sayin’ that I’d learned real early that there’s a lot a’ things that you can do but even a lot of those you better not touch. I guess when he met me it was probably the first time he ever thought of that ‘cause he acted like I’d just gone and tossed all a’ my marbles out with the bath water and the baby too for that matter. By the time I’d taken a big bite out that sweet, juicy berry; I’d lost my head and fallen into the trap. I got caught up in the whirlwind, tossed up high and I’ve not come down yet. Before I realized it, he was hangin’ his clothes on the back of the bedroom chair and it took a friend to tell me that he was livin’ with me, bless his heart. Why, it wasn’t long before he was tellin’ the cat to “sindow” and my friends to “shit out a’ here”. He made himself right at home. My ex-husband said it was as though an invadin’ tribe had taken over, labeled him Romeo and said “it” was all about my orgasm. Well, maybe he’s right. My best friend said she thought she was havin’ a vision of the zoot-suit wolf, and another friend said that the demi-god of chaos had just landed on planet earth. Why, he was New Year’s Eve to their bedtime. Well, Mom said he was just a child. But what she doesn’t know we won’t tell now; will we?

Well, I’ve always considered myself a sensible kind a’ girl but after dancin’ with him for one night, I was after him like a bee after honey. Now, there’s lots a’ good dancers out there to be sure but there was somethin’ about the way he moved that… and the way he rocked the… and the way he pressed on… I don’t know but it hooked me. Before I knew it, he was introducin’ me around the club as his woman, singin’ in my mouth and kissin’ me with a big gulp of beer in his mouth slowly lettin’ it trickle into my mouth makin’ me weak all over lettin’ him just eat me up. I just plain forgot myself and even forgot my name and where I’d come from. He took my jacket, wore my pants and tennis shoes and fine, honey, he looked fine, even in his bright neon pink baseball cap tipped up on the top of his head, lettin’ his black curls fall loose. Well now, the girls at the office thought it was a good idea if I turned that man out and got something a little less black under the nails, someone who spoke our language. But I’ll tell you this, when the light is right, when the love is right, when the party is right, and everyone is uptight then he can be whatever you need him to be.

Well now, he’d bought a car, well sorta. It was a cherry red Hyundai bein’ sold for parts but he transformed that baby into the slickest ride ever. Now, I’ve never been much for thrill rides but baby, I liked this one. He had me and my girlfriends screamin’ and squealin’ and quiverin’ in places that had long been sleepin’. It was a magic carpet ride… out a’ the old and into the new, baby! I guess we spent more time in that car than we did in the house. It seemed like in that car there were no rules, no road rules and no rules for us.

Well, one time we were sailin’ down MLK Boulevard at about 80 miles per hour at 2.00 am, you see, he was hungry. It wasn’t long before the big police started shinin’ their lights on our trip and blowin’ the siren. So, we pulled over on the ramp of the bridge. I’d lived all my life without ever gettin’ as close as a block away from the authorities, so I was just a little nervous. Not him, I guess he’d done this before… he was ready anyway. He had a little bronze rectangle with some sort of a saint on it tucked neatly up in the headliner a’ the car. That police officer was at least seven feet tall, includin’ his hat, his uniform so tight, pants tucked down inside a’ his knee-high boots, a gun, a club, a stun gun, a pair a’ handcuffs, a walkie-talkie, pockets full a’ pens, a ticket tablet, a badge that shown like a fallen star and god only knows what else. He jingled like Bo-Jangles when he walked as he snuck up on the driver’s side a’ the car. “Can I see your license”, he said. Well, now you know as well as I do that he didn’t have a license and besides that, he couldn’t read the signs on the road anyway. “No hablo ingles”, he said with the sweetest damned smile that you ever have seen. I mumbled somethin’ about him bein’ a refugee and some lie about my shoulder hurtin’ and so he had to drive blah, blah, blah, blah and he didn’t give us a ticket or anything! The biggest arm in the world came into the car and a voice out of either hell or heaven said, “YOU DRIVE”. Well, I haven’t ever driven a stick before, but we changed seats and I started the car as Mr. Scary stalked off to his patrol car. We lurched around there on the ramp ‘til I said, “YOU DRIVE”, we switched seats again and off we went to buy a hamburger laughin’ at how we had got away with murder.

Now, at the time I didn’t think everything was how it should be. Just when I thought he had gone a little too far and he should have to pay for pushin’ the boundaries a little too hard, well, he just slipped on under the fence and came out on the other side where the grass was just a little greener. Like the time the girls in front of us in the line at Burger King just weren’t movin’ and he was hungry and wanted his food. When they closed down the store and called the police I thought we were done for. He had a bottle a’ rum under the seat and a’ empty hole where his stomach used to be, and he wanted to fill it and he wanted to fill it right now. Well, things were movin’ just a little too slow for him so he gave that car waitin’ at the drive-up window a little shove. Well, when that didn’t work he pushed again and then again and that car didn’t budge an inch. Well, he was as determined as you can get, and he was a pushin’ and pushin’ and to my surprise the girls got out a’ the car, left it sittin’ right there in front a’ the window and went and sat on the grass by the exit sign. Now, he thought he was never goin’ to get any food. Well, he was honkin’ and carryin’ on when not just one but two police cars pulled up and four policemen got out and wanted to know what in the hell could be goin’ on to stop the flow of fast food junkies. The girls talked to them first and said this guy behind them thought he was god or somethin’ and was tryin’ to kill the baby just to get his “Whopper”, and he was drunk, and he was this and the other. Well, I wasn’t havin’ none of it and I walked off down the street shakin’ my head and wishin’ I wasn’t there. I watched as he pointed at me and tried to tell them in Spanish that he was on a break from work. NOT!!!! And that he had to hurry, or he would lose his job. NOT!!!! And what do you know if they didn’t tell those girls that this guy was just as nice as could be and they could tell perfectly well that he was not drunk because they are officers of the law and they are trained to know when a person is drunk and they believe that they’d better get off’n their little stinkin’ asses and get back in their car and let this fine gentleman get his food and get back to work and that next time they better think about what others might need and not be so selfish and that he was as harmless as a little spider… HA! Well, then they told those people inside the burger joint to get this man his food right away and we were off before you know it, me not so happy but he smilin’ around big mouthfuls of hot juicy meat. Yeah, he was gettin to know his way around real good. He worked all right but just not in the way most of us here are used to doin’ it.

For a boy without the language but a whole lotta’ street smarts, he figured out ways to get what he needed. He already had me, baby. I wasn’t goin’ nowhere even if I did think I was goin’ to my grave sometimes. Why, by now I had candles burnin’, glasses a’ clear as crystal water sittin’ on the top shelf and a statue a’ San Lazaro sittin’ on the floor, herbs layin’ around, rum sprayed all over the house, half smoked cigars and plastic flowers and loud music and drums and the best fuckin’ I’d ever had. Why, I was even startin’ to believe everythin’ he said. Well, wouldn’t you? Like I said, he worked. Anyway, he worked it.

He’d go down to the corner in the slummin’ side a town and wait with the rest a’ the guys for rich folks to come pick ‘em up to do some work or the other. (If only the girls in the office knew I was lovin’ a man like that!) Well, he wasn’t about to let anybody get the best a’ him. He’d learned way before that you can get the best a’ them if you just know how to do it. When those cars would drive up those boys would run to see who could get to the car first and start screamin’, all a’ them, “I can do it!” “I can do it!” And hardly any of them knew what anybody even wanted but they could do it. Well, he was skinny and new on the corner, but he was smart. Well, and the pay was nothin’ to write home about and not even enough to satisfy a boy with even the smallest appetite. So, he told the guys that if they all got together and held out for a lot more money those folks would have to pay it if they wanted to use their strong backs. So, everyone said that it was a good idea and they had a kind a’ strike right there on the corner full of beer cans, and fast food wrappers and broken dreams and it was true what he said. Those folks need them so bad they paid more than ever before, and he would always get the best jobs because he learned to say, “I pain’, I tile y marmol, I dig, I was’, I cut, I run… I can do it!” even when he couldn’t. And most of the time he came home with money in his pocket. He had a way to get where he wanted where it looked likely that there was just no way. It’s like the time he was paintin’ apartments and his boss sent him to get food for the whole crew. The whole world on this tiny corner on a street in our town came to a halt because no matter what, he was goin’ to get his food.

Well, the cars were lined up for a mile down the street out into rushin’ traffic, everyone with only a half hour to eat. Everyone waitin’ to get their food and he was just sittin’ on the hood of his car and he wasn’t goin’ nowhere until he got what he came for. Now, he loved hamburgers, and not much made him more happy than that. It’s one a’ those things that he knew we all were entitled to get. Well, he had pulled up to the squawkin’ speaker and said, “Dame doce whoppers, cinco cocas medianas, sies oransh, no ice, doce frensh fries” and all he heard back was, “What?” He said it again… and again cracked back a voice on the other end, “What?” He said it again but this time he yelled, “Dame doce whoppers, cinco cocas medianas, seis oransh no ice y doce frensh fries motha-fucka!” “What?” Well, right then he threw his car into gear and squealed up in front a’ the window where there was a real live human being and he stuck his head right out a’ the window and practically in the drive-up window, threw the list his boss had made for him at the face lookin’ back out at him and he said in a voice so slow and calm that even a baby would give up his candy, “Dame doce fuckin’ whoppers, cinco funkin’ cocas medianas, seis motha fuckin’ oransh no ice y doce hijo de puta frensh fries motha fucka.”

That mouth said, “We don’t take orders like this”, and the window closed just about right on his nose.

Well, he got out a’ his car pushed that pink neon cap back lettin’ his hair fall out over his brown forehead, hiked up his pants and hopped up onto the hood a’ that car and leaned back on the windshield just like he was takin’ in a bit a’ sun on a cruise-ship and decided to wait while they got his food out to him. Well, it began to creep little by little into his head that things weren’t goin’ quite as he planned when the window didn’t open and the folks waitin’ in line started honkin’ and screamin ’at him to get the fuck back into his car and to get his mother fuckin’ car outta the way before they beat his mother fuckin’ ass. But he just laid there waitin’. But at the same time that a little old white-haired lady all bent over knocked on the window and said she wanted to read the order for him, the police showed up to find out why there was such a jam out in the street. Well, there was somethin’ in his eyes all twinklin’ or in that handsome face or in the way his black shiny hair curled around his temples or the white gleamy teeth behind crimson lips that brought that little old lady alive and she explained the whole thing. Standin’ up just a little taller she said, “This man only was tryin’ to get his food, officers, and holy Jesus how they give this boy a troubled time.” Well, the officers, they personally went to the window and said, “Give us that goddam list, son.” And they read it and waited right there until he had his order in the car and sped off laughin’, no license, no insurance and citizen of no place at all, all the way back to work to tell another one of his hard to believe stories when they ask him what took him so goddam long. Why, he even said he thought he saw that little old lady wink at him as she turned around with a look on her face that he had seen many times before.

You’re probably sayin’, “Doesn’t he ever get taken down?” Well, yeah… but no, because he comes up smellin’ like new every time. Yeah, he’s been to stand in front a’ the judge, but the cops just never show up to say what he’s done.

Well, it’s been fun tellin’ all a’ this but I’ve got to stop because I could go on. He makes a way out when everyone says, “That’s no way out. You can’t do that”, and he does. He’s got us all buildin’ altars, wearin’ red string around our wrists, tearin’ our clothes off in the river, we’ve got packets tied up in red string and shot through with needles restin’ in the freezer or under the roots of a tree. Eleggua’s behind the front door and the nganga’s full a’ round, smooth stones. And now that he’s gone, we know that he taught us. When we sit around the table talkin’ and laughin’ and cryin’ and rememberin’, we know we didn’t really see him while he was here. We eat congri, light candles and pray for his return. He’s gone but I can tell you he is still here. The trickster lives.

Commentary

In this essay I would like to explore the possibilities of a correlation between a story of a young Cubans’ life and the trickster figure. The story allows quick snapshots, microseconds, as the camera lens opens and quickly closes as we peer into his days from childhood to young adulthood. I would suggest that this portrayal is one in which some of the characteristics of the trickster are evident though this tale is, to the core, secular. It does not contain etiological explanations of the world as it is except as far as the protagonist creates his own reality and changes the people and the lives of those he invites in. This is precisely why I chose to explore the trickster as a secular personality. It is also an opportunity to discover, to a finite degree, the functions of Ìjàpá the tortoise.

The analysis of my subject as a worldly trickster is justified by an argument posited by Ropo Sekoni.1 He maintains that, though Esu and Ìjàpá the tortoise, two Yoruba folklore tricksters, share among other similarities, a “view that everything is alterable”, there is a clear distinction between the contexts in which they operate: Esu is a mythoreligious trickster while Ìjàpá is secular. Ìjàpá’s connection with Esu in Yoruba folktales is one of apprentice to mentor or teacher. After completing his apprenticeship with Esu, a folktale tells us, Ìjàpá swears never to have another thing to do with Esu again. They part ways, which is the end of Esu’s domination of Ìjàpá. Another point made by Sekoni is that every member of Yoruba society is a “potential narrator” of Ìjàpá tales. These are stories told by ordinary people about every day experiences. They are intended to teach children lessons of morality.2 His argument holds out that Ìjàpá is an example to the Yoruba about what one should not do but also about what, sometimes, one must do.3 The audience usually reacts in two ways to Ìjàpá. Either they reject his “reprehensible, anti-social, anti-human traits”4 and they laugh at him and condemn him, or they sympathize with him. As something with which to identify, he is viewed as a victim of circumstance. Whether he is successful in his protest against society or whether his actions are appropriate, he is deemed courageous in his attempt to break repression or absolute norm”.5 He is, according to Sekoni, rebellious because he is marginalized and less powerful because of social hierarchy and because of his weight and size.6 He is in “the underdog position”, “a victim of domination”,7 and “there is always a need for the underdog to challenge, confront and even subvert the system that does not recognize him”.8 On the other hand, the stories of Esu are told only by initiates or by cult members and are concerned mainly with prehistoric and metaphysical space.9

Àjàpá10 is appealing to the Yoruba because he displays “anti-social behaviors” that allow for commentary but also because “simultaneously [he] “enables them to dramatize remarkable qualities that could stand those who possess them in good stead in coping with a difficult world.”11 One of his best and most useful qualities is that of song. Àjàpá “by means of his musicianship is able to cast powerful spells over individuals and whole communities, even on other worldly beings, so they forget themselves and their present purpose, abandoning themselves to the rhythm of his songs.”12 Pelton’s colorful expressions for Esu are also appropriate here as appraisals of the main character, “He is fecund and beautiful”, “the flamboyance and exuberance of his dance, it’s agility and playful eroticism, embody his power to foment adultery and seduction…” “He is a troublemaker, a disturber of the peace, and disrupter of harmony, his playfulness and his rebellious[ness] and defiant nature are expressed in [his] dance.13

From my studies and subjective experiences, I have surmised that trickster characters are plentiful among the population in Cuba. Circumstances warrant wily ways and wily thinking. Documentations in ethnographic accounts, in literature and film produced within and without Cuba abound with them. Three such examples are historian C. Peter Ripley’s accounts of trips to Cuba that shed light on the successful tactics used by young men and women in order to trick the system in order to surmount arduous restrictions.14 Author Reynaldo Arenas, created a book that revealed the secrets of the underworld of homosexuals in post-revolutionary Cuba.15 Other examples of trickster personages are in the films of Tomás Gutiérrez Aleas, which “poin[t] out the foibles of Cuban society”.16 These illustrate that because of circumstances beyond their control, men, women and even children learn to trick the system to make a living, stay out of jail, to live as they wish and to get what they need. This is a world where doctors are taxi drivers, women are homemakers by day and prostitutes by night and best friends and even family members inform on one another, where everything is not as it seems but is as it is. When you do not have anything, you can do everything. According to Ramiro, the protagonist of my story, the poor can do what the rich can never do.

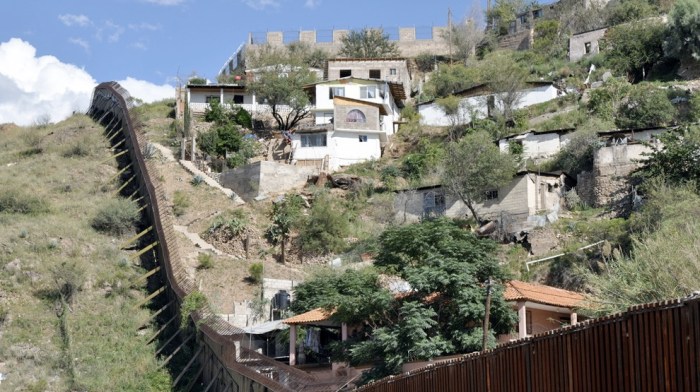

My account places the central character, Eulogio Ramiro Verdecia Rivero,17 in a hostile environment first, within his family, his community and finally in the larger world. In each setting, he must create his own understanding, to interpret his surroundings and function in them to survive. He is dropped suddenly into unexpected conflicts always expecting paradise, but where even a series of small miscalculations could mean disaster. He functions best in his home environs because he understands what is expected of him as a member of that community, but he must act outside of the absolute norm. It is also here that he learns the tricks of survival that will see him through more challenging times ahead and produce lessons of social morality just as our trickster Ìjàpá does. He grew up in Cuba after the United States imposed a total embargo of U.S. trade with the island in 1962. The collapse of the Soviet Union resulted in the 1990 imposition of austerity measures placed on the Cuban people called the “Special Period”.18 The embargo which amounted to a blockade, tightened its strangle hold on the Cuban people when in 1992 a legislative bill was passed to “end corporate subsidiary trade with Cuba (70% of which is in foods and medicines)”19, and put a sanction on any country who trades at a Cuban port. The result of the blockade was not the downfall of the charismatic “maximum leader” Fidel Castro and his supposed communist government, but has resulted rather in the devastation of the already unstable economy. The main character of the story represents the capacity of a people to survive with ingenuity, flexibility and adaptability in a harsh environment within the island and marginalized by the world. Where harsh measures are enforced, it is not beyond imagination to believe that a people who have been deprived of freedom of movement, sufficient food, clothing and medicines enough to survive with dignity, would develop strategies for getting around the oppression. The oppressor, in this instance, is not only his mother, but is also the government who becomes the opponent and the police it’s agents. The only way of striking back or providing for his needs is to be smarter than the system. Two years after Ramiro leaves the island, an elderly man on the street in Havana in 1996 describes the situation in Cuba succinctly, “Right now we have the special period and we laugh, we make love, we dance, and we drink, and we go out and we get a piece of bread with some buccula and we keep going. We don’t take life so hard. We play along, and we crack jokes, a psychological thing of the Cuban people. And we are always on the go and we’re always moving.” This is just one strategy, the other is to try to outsmart the enemy, or in other words, be tricky.

When Ramiro leaves Cuba by raft and unexpectedly ends up in Guantanamo Bay, a U.S. Army Camp, the difficulties multiply. His new nemesis becomes the U.S. army officers and the restrictions of a refugee camp as well as other refugees. Upon his arrival in the U.S., he faces new obstacles. It is still the government and the police whom he needs to outsmart, but he is also in a mêlée with new cultural norms. Though he believed that all his troubles would be over once he reached the U. S., he was greatly mistaken. If I may, much like Brer Rabbit, Ramiro, “…defeats his enemies with a superior intelligence growing from a total understanding of his hostile environment”.20 Uncle Remus explains, “In dis worril, lots er fokes is gotter suffer fer udder fokes sins. Look like hit’s mighty onwrong; but hit’s des dat away. Tribalashun seem like she’s a waitin’ roun’ de cornder fer to ketch one en all un us honey.”21 Had he heard Uncle Remus’ explanation of the injustices suffered in this life he would have understood perfectly what he was talking about: he was accustomed to want and living without, not because he was incapable of making a living, but because he was prohibited by the circumstances into which he was born in Cuba and then as a refugee in the United States. Therefore, a tactic taken to get his needs met: food, sex and a place to live is, as Pelton describes it “of phallic boasting and [a] manhandling of everyday reality”.22

I was usually angry with him because I could not understand why he never seemed to have to pay the consequences for his actions. While others do without a pig on New Year’s Eve, he finds a way to get one by convincing a friend to drive him into the mountains. In Cuba, cars are few and gas is expensive. While others spend months in jail for crossing the Canadian border, he slips back and forth as though invisible. He gambles and wins. When he does receive a ticket for a traffic infraction, the police do not show up to charge him. When his parole expires, he goes to immigration to renew it and though they refuse to, he can leave without being deported. He pushes into the cars in line ahead of him at Burger King to get his food faster. He completely stops a line of people on their lunch break to get served. He speeds down the city streets confident that his icon of La Virgen de Caridad, patron saint of Cuba, will protect him and it does. He drives up on the sidewalk in front of a Seven Eleven to get to an exit that does not exist for anyone else but him. He is never discouraged by setbacks; as a trickster he, “…gives us crucial insight into our capacity for error and our need to accept it as part of this existence”.23 He is a square dance caller, a prophet, and preacher and cruise director. He is the sacred clown,24 what we wish we could be; doing what we wish we could dare to do. Now that I am no longer a part of his antics, I can laugh at them. Lame Deer, an American Indian, enlightens those of us who have not had the experience of extreme oppression, “For people who are poor as us, who have lost everything, who had to endure so much death and sadness, laughter is a precious gift.” “To us a clown is somebody sacred, funny, powerful, holy, shameful, visionary. Fooling around, a clown is really performing a spiritual ceremony.”25

He moved in on me without my verbal permission, though somehow, I must have asked for it. He took over the stereo, the kitchen, my car, and my life. He sang in my mouth, exposed my soft spots and flayed me wide open; I died and was reborn. Using Pelton’s words again, “His “energy can carry passengers along an open road as well as dump them in the river.”26 He made me laugh and cry. Startled, I stepped into a world of need and passion that I had no idea existed though it lay dormant inside of me all the time. He opened a door into a world of tricksters and gods, of music and dance, of abandon and chaos. He has all of us, who had the pleasure to cross his path, building altars, wearing red string around our waists and wrists and tearing our clothes off in rivers. We have packets of yellow paper wrapped with red thread resting in the freezer or buried in the roots of a tree. Images of Eleggua hide behind our front doors. Now that he is gone we sit around the table and remember his antics and we laugh and we cry because he is not with us anymore, but in fact we did not see him clearly while he was here. Mom kept chanting that he acted like a child. Friends called him a zoot-suit wolf or diosito (small god) of chaos. The police called him a criminal. And my ex-husband said that a tribe had invaded, called him Romeo and said “it” was all about my orgasm. And still others thought he was an opportunist. I suppose in all facets of his being, he fits the description: “Sometimes trickster is creator, sometimes destroyer, sometimes trickster is a hero and sometimes a fool”.27

Therefore, this is a story of what is possible through believing that anything can be done, that boundaries are to be challenged, knowing one’s power and getting what one needs by “tricksterness”: use of his sexual prowess, by a developed sense of possibilities and subsuming authority to a posture of complicity. Representatives or agents of power are made to look like bungling incompetent fools and are deceived by just a smile. Pushing the boundaries, he is fearless because he is already marginalized; he is between two worlds; neither a citizen of Cuba nor the United States. All of his American friends scream, “You can’t do that while he is in the process of doing it, “he is a lawless fool”.28 By observing the trickster, we see him act out his “capacity” to be wise and foolish, good and evil, strong and weak, moral and amoral, social and asocial.29 “There is nothing written”, he says. “Death holds no fear.”

NOTES

1 Sekoni, Ropo. Folk Poetics: A Sociosemiotic Study of Yoruba Trickster Tales. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1994.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid. 9

4 Ibid. 23

5 Ibid. 23

6 Ibid. 8

7 Ibid. 7

8 Ibid. 8

9 Ibid. 7

10 Owomoyela, Oyekan. Yoruba Trickster Tales. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997. x This is another spelling for Ìjàpá, as well as Alájàpa, Ahun, Abaun or Alábaun.

11 Owomoyela. xiv

12 Ibid. xiii

13 Pelton, Robert A. The Trickster in West Africa: A Study of Mythic Irony and Sacred Delight. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980. 130-131

14 Ripley, C. Peter. Conversations with Cuba. Athens: University of Georgia Press. 1999.

15 Arenas, Reynaldo. Before Night Falls.

16 Brennan, Sandra. “Artist Biography and Filmography: All Movie Guide”.

http://aol.com/mv/filmography.jhtml; I recommend: “Fresas y Chocolate”, “Guantanamera”, “La Ultima Cena”, “Cartas Del Parque”, “Los Sobrevivientes”.

17 I have permission from the informant to use his actual name. This is a small part of a larger work in progress.

18 Pérez, Louis A. Jr. Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995. 383-387

19 Prada, Pedro. Island Under Siege: The U.S. Blockade of Cuba. Melbourne: Ocean Press, 1995. 12

20 Hemenway, Robert. “Author, Teller and Hero”. In Uncle Remus: His Songs and His Sayings. New York: Penguin Books, 1982. 9

21 Ibid. 102

22 Pelton. 27

23 Lunquist, Susan Eversten. “Trickster as Archetype, Myth and Life Symbol”. In Trickster: Transformation as Archetype. San Francisco: Mellen Research University Press, 1991. 29

24 Ibid. 94

25 Lame Deer and Richard Erdoes. Lame Deer: Seeker of Visions. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972. As quoted in Lunquist. 27-28

26 Pelton. 132

27 Lunquist 25

28 Pelton. 37

29 Lunquist. 26

References

Harris, Joel Chandler. Uncle Remus: His Songs and His Sayings. New York: Penguin Books, 1982.

Hemenway, Robert. “Author, Teller, Hero”. In Uncle Remus: His Songs and His Sayings. New York: Penguin Books, 1982.

Lunquist, Suzanne Eversten. Trickster: The Transformation Archetype. San Francisco, Mellen Research University Press, 1991.

Owomoyela, Oyekan. Yoruba Trickster Tales. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.1997.

Pelton, Robert D. The Trickster in West Africa: A Study of Mythic Irony and Sacred Delight. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980.

Perez, Louis A. Jr. Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Prada, Pedro. Island Under Siege: The U.S. Blockade of Cuba. Melbourne, Ocean Press, 1995.

Ripley, C. Peter. Conversations with Cuba. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1999.

Sekoni, Ropo. A Sociosemiotic Study of Yoruba Trickster Tales. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1994.

Spinks, C. W. Jr. Semiosis, Marginal Signs, and the Trickster: A Dagger of the Mind. London, Macmillan, 1991

The End